Part of the long term project “With the Name of a Flower”.

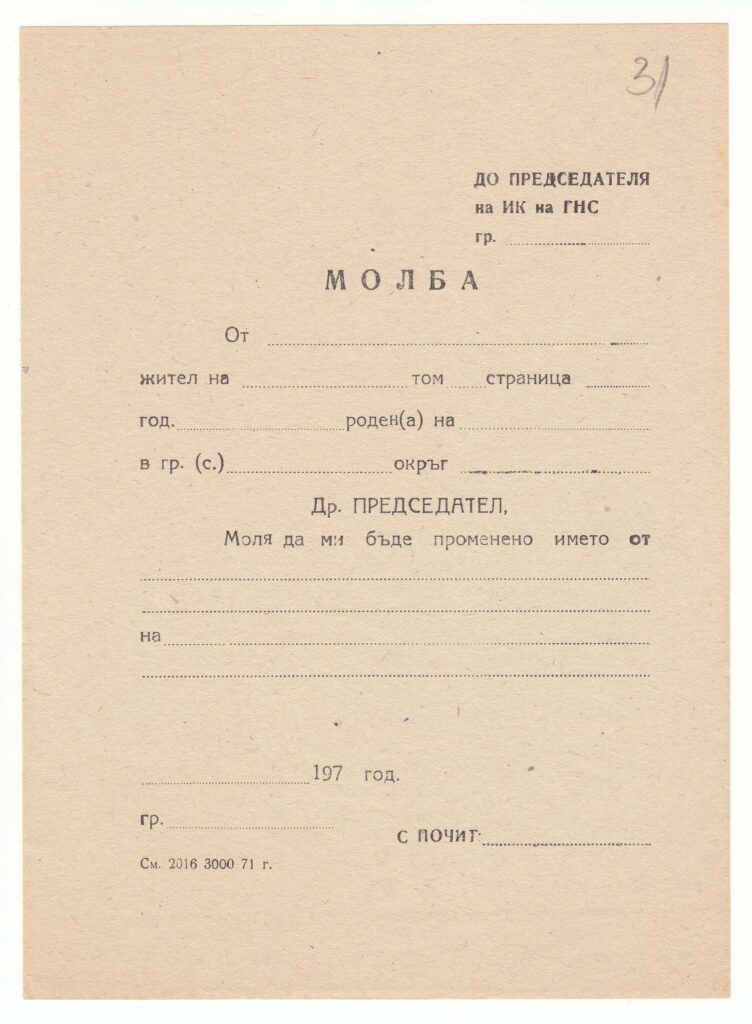

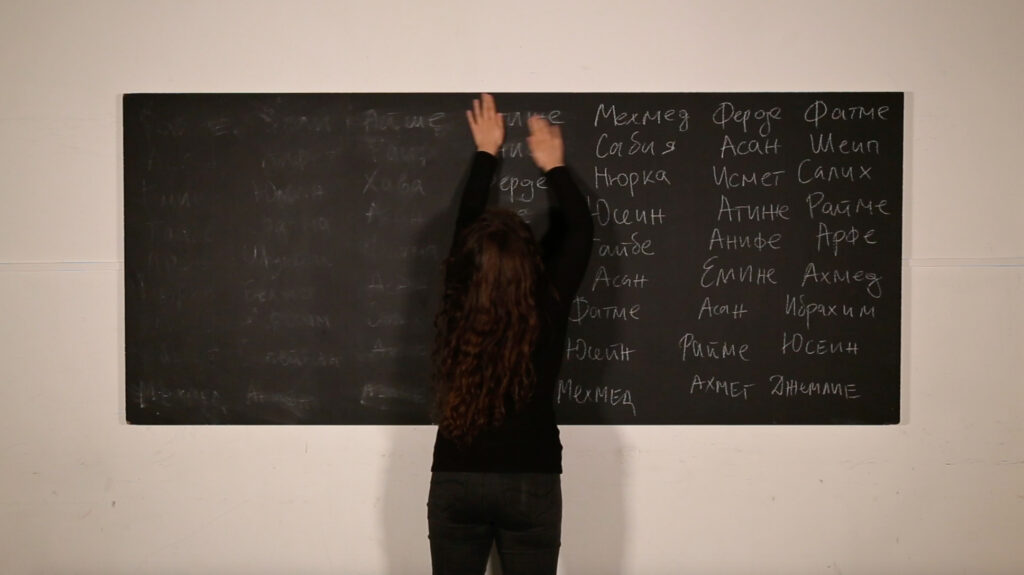

With the Name of a Flower is a personal story of the artist and photographer Vera Hadzhiyska. Her project explores the forced name changes (from Muslim to Slavic names) of the Muslim population in Bulgaria in the period between 1912-1989, and the effects they continue to have on people’s lives, identity forming and sense of belonging today.

A few years ago, Vera was interviewing her grandparents about their lives. It was during these interviews that they spoke of this issue. This sparked Vera’s curiosity. Only afterwards when she started researching the reason for these name changes did she find out about the process of the multiple name changing: a systematic campaign by the Bulgarian authorities throughout the 20th century. A majority of the Bulgarian Muslim population was affected by this. Given that name changing was forced on the population, it is difficult to find official numbers and statistics about the extent this affected Bulgarian society.

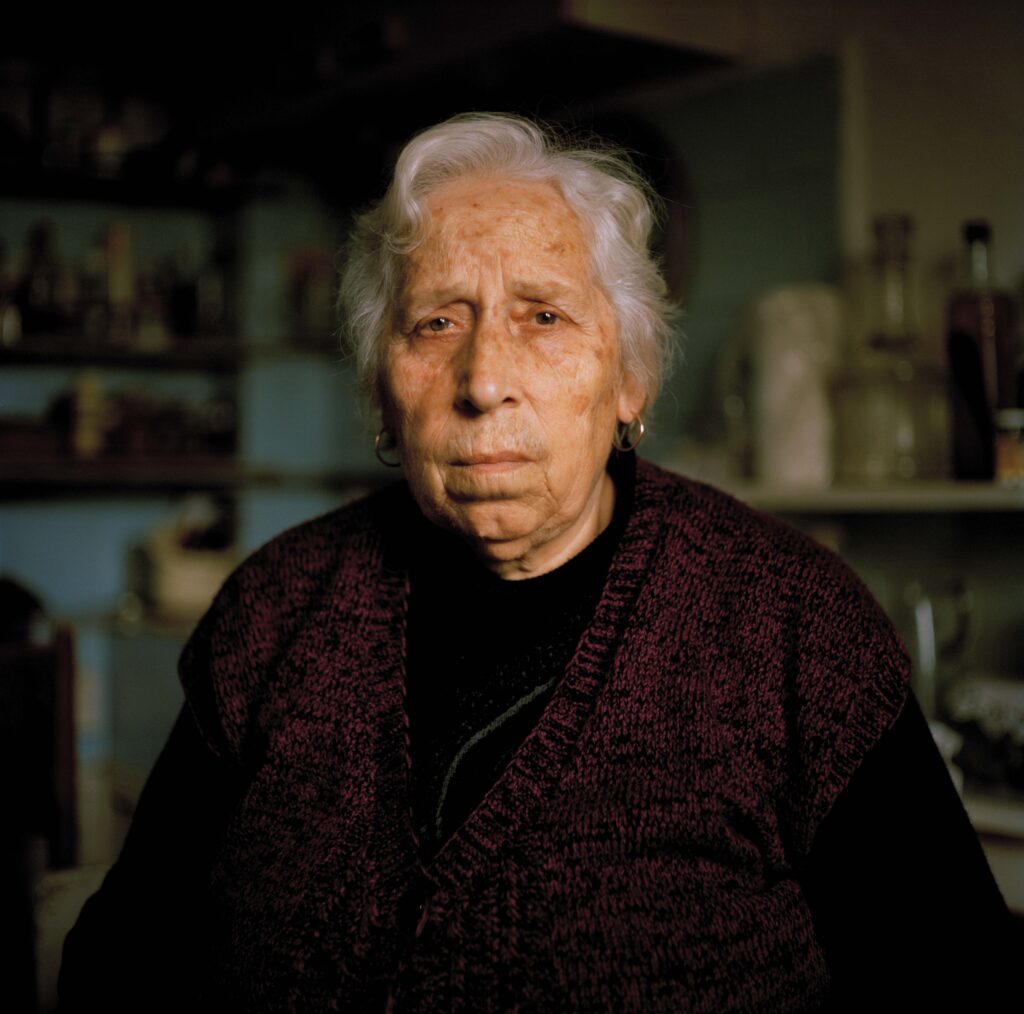

For Vera, finding out that her family came from the Bulgarian Muslim community came as a huge surprise. She had never been told that her family were Muslim, once bearing Muslim names. In fact, Vera remembers growing up celebrating all religious traditions, both Orthodox Christian and Muslim religious holidays.

“… however, nobody had explained to me that they were part of the Islam traditions, so I just thought they were something normal. And since Bulgaria’s official holidays are Orthodox Christian, we’ve always celebrated them as well. The celebration of Ramadan and Eid was present but unnamed (unspoken of). Only looking back now I realise it.” – Vera Hadzhiyska, winner 2021 VID Grant.

This was the reality of Communism where the ideology was propagated over any form of religious belief. Therefore, the name change campaign had a purpose to standardize the diversity of Bulgarian identity and to create a Slavic, Orthodox ethnic standard majority.

“[…] based on my observations and research, I think what the state wanted to achieve by changing the Muslim names of people to Bulgarian ones was to erase the obvious symbols of Islam visible in the Bulgarian society. And to be fair, it worked to a big extent. Many people from my family […] hide that they are Muslim/Pomak. After the name changes some of them buried that part of their identity. I think they only share or acknowledge it when they are among other Pomaks or within the family circle. For outsiders and the wider society, that part of their heritage and identity is concealed.” – Vera Hadzhiyska, winner 2021 VID Grant.

Part of the long term project “With the Name of a Flower”.

Vera started studying her own family history and heritage more in depth. She interviewed members of her family and dug deeper into the state archives in Bulgaria to make sense of the conversion and its impact on the older members of her family. She studied the trauma that has been passed down to her own generation and in her family, observing how her sense of identity and belonging differs from that of her grandparents and parents.Through this study, Vera found out that it was in 1971 that her grandparents were made to change their names from Muslim to Slavic.

The systematic forced name change campaign of the Bulgarian authorities remains a big taboo within contemporary Bulgarian society even today. There are many families who, to this day, dread discussing the issue openly in fear of repercussions and retribution both from government and society at large.

“In the Balkans we share a collective memory of the Ottoman rule, however each country has its own narrative and experience of it. I hope my research into the name changes in Bulgaria will expand to look into the name-changing campaigns and migrations that occurred in neighbouring countries like Greece and Turkey, where name-changes were also enforced. There is a certain intermixing and diaspora of the people in the Balkans that makes us close to one another. I think the relationship between religious and national identity in the Balkans is something worth exploring, especially in connection to the Ottoman Rule’s religion-centred society and the Communist regime’s state atheism.” – Vera Hadzhiyska, winner 2021 VID Grant.

Part of the long term project “With the Name of a Flower”.

Vera’s documentation of the name change in her broader family and her community in Bulgaria takes us into a darker side of Bulgarian history. Her work incorporates beautiful and poetic imagery complemented with interviews by family members and moving images. Her photography is intimate and evocative; her colours are rich, warm and vibrant; and through composition and styling they clearly communicate Vera’s love of home, family and tradition, and her concern for the erasure of diversity and difference.

The VID Foundation is delighted to offer the VID Grant to Vera for uncovering, analyzing and taking us into this dark history through her own personal family story. Her project brings into focus this localised history.

Part of the long term project “With the Name of a Flower”.

Stories such as these are important to bring into the public realm as they can be quietly overlooked. Vera takes a unique approach to sharing such delicate family narratives whilst proposing something far deeper, signalling the impact on an individual as well as a family and community, when their identity is directly affected by the state. We hope that such work uncovering often untold stories and taboos can inspire and empower others across the Balkan region to speak out against oppression and state censure on identity.

Vera Hadzhiyska is a Bulgarian multi-disciplinary artist and curator based in England. She holds a Bachelors (2017) and Masters degree in Photography (2019) from the University of Portsmouth. Her practice is informed by the study of migration, cultural and national identity, history and collective memory. She uses photography, performance, archival documents, audio and video installations to examine historical and political events in Bulgaria and Eastern Europe, their impact on people’s lives and identity.